Saving the Wild Salmon: Bristol Bay Contends with Pebble Mine Proposal

May 12, 2020

Stephanie Armstrong, Intern,

Ed Yowell, Chair,

SFUSA Food and Farm Policy Working Group

Save What You Love – Bristol Bay

This story and call-to-action is about a salmon ecosystem that is sacred, worthy of your love, and worthwhile to save.

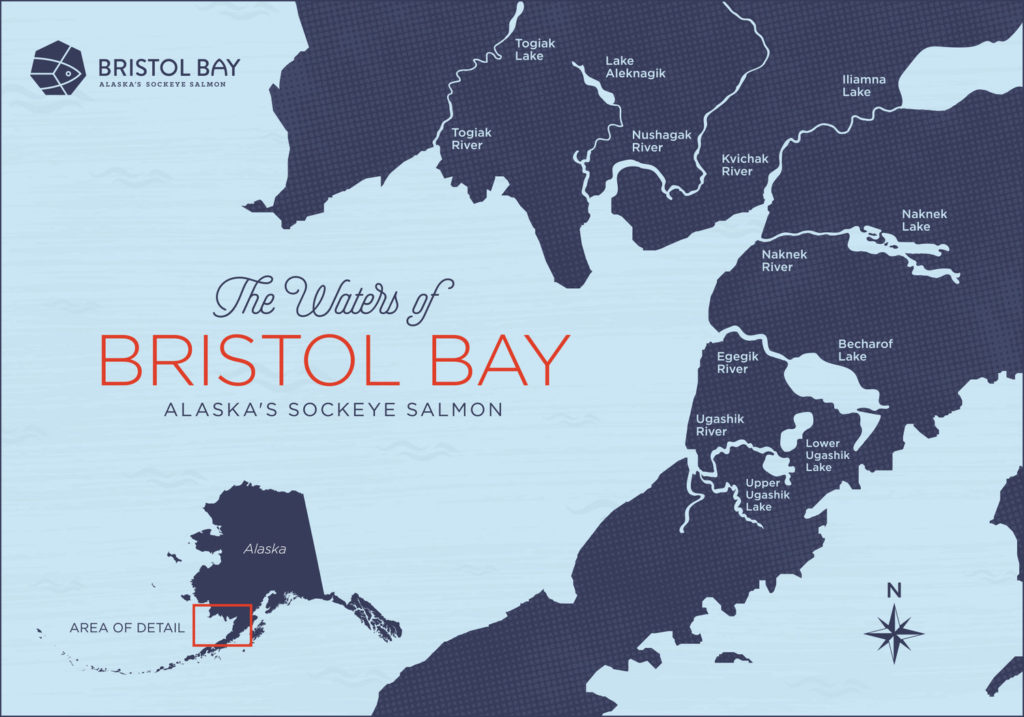

Image from bristolbaysockeye.org

On the shores of southwest Alaska, Bristol Bay is home to the largest wild salmon fishery in the world. The waterways support thousands of fishers, 25 tribes, and millions of salmon. Generating over 14,000 jobs and $1 billion in economic activity, Bristol Bay lures fishers from across the United States to participate in the summer harvest. Up to sixty million salmon return to the area each year to spawn, providing a regenerative food source not only for us, but for at least 138 other species in ocean, freshwater, and land habitats.

Salmon is a unique keystone species, which is why Mark Titus created The Wild, a film about saving Bristol Bay from mining operations that endanger the people, the salmon, and the ecosystem at large. The film is an ode to the persistence of salmon and an opposition to Pebble Mine – a proposal for North America’s largest open-pit mine “directly in the headwaters of the most prodigious wild sockeye salmon run in the world.” Kicking off the Save What You Love Tour with virtual screenings on June 5th, The Wild asks, “How do we reconcile human separation from the natural world that sustains us – and if we can change course – how do we save what remains?”

As a Bristol Bay fisher, Kevin Scribner, 2019 Snailblazer and Slow Fish member, has written a series of articles about the Alaskan community he loves. Kevin reminds us that we are all connected to the land (and water) where our food originates.

We Slow Food & Fish folks believe we are what we eat, and joyfully so. I also believe we are from where we eat. When you eat Bristol Bay salmon, you become connected to Bristol Bay. No matter where you are, how near or far from Bristol Bay, you become one with the Bay’s communities, the salmon, and the entire ecosystem... We Are Bristol Bay, we are legion, and we are joyful!

Slow Food stands with the Bristol Bay community in their efforts against Pebble Mine. We support the rights of the residents to determine what becomes of their land, the livelihood of responsible fishers, and the interconnected ecosystem that relies on salmon for its well-being. Read on to discover why we should save Bristol Bay, and how you can take urgent action to stand with us.

The Pebble Mine Proposal

The status of Pebble Mine has been rocky since Pebble Limited Partnership (Pebble) proposed the operation over a decade ago. Despite consistent opposition from the community, Pebble continues pushing to develop the vast deposit, and the long-fought battle will come to a head this summer.

The original Pebble Mine plan was developed in 2006. The company sought to access an enormous deposit – 11 million tons – of copper, gold, and molybdenum in Bristol Bay. Indigenous tribes, fishers, and other groups petitioned Obama’s EPA to review the plan under the Clean Water Act. In the EPA’s Watershed Assessment of the Pebble deposit, spanning four years of research, external peer reviews, community meetings, and over one million public comments, the agency determined by-products from the mine “would result in complete loss of fish habitat” and mine waste “would significantly impair the fish habitat functions of other streams, wetlands, and aquatic resources. All of these losses would be irreversible.” The EPA proposed mining restrictions to protect Bristol Bay, and received a lawsuit from Pebble in response.

In 2017, Trump’s EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt met with Pebble CEO Tom Collier without consulting his staff or scientists. Their meeting ended in a devastating settlement. The EPA’s water protection process and proposed mining restrictions were suspended until the Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps) processes Pebble’s mining application and issues a final environmental impact statement. Pebble submitted its application by the end of 2017.

In 2019, following years of lobbying by Pebble, the Corps released a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) on the potential impacts of Pebble Mine. Bristol Bay residents, fishers, scientific experts, and the public spoke up en masse. Numerous criticisms were launched at the EIS shortcomings, detailed below. Wild Salmon Center published a report revealing attempts by Pebble and federal agencies to review the Pebble Mine application before the end of Trump’s term with “a permitting process that is faster than any project of this size and type in American history.”

Currently, fishers are focused on day-to-day operations as the seafood industry reels from Covid-19. The Bristol Bay community is wondering whether there will be a salmon season this summer. Incoming workers pose a health threat and locals worry about the lack of medical resources and vulnerability of their people. With everybody focused on the pandemic, the Pebble Mine permitting process proceeds. The Corps is on track to complete the finalized EIS by June, despite criticisms against their draft statement.

EIS Pitfalls

In its 2019 report, Wild Salmon Center lists these major concerns, among others, over the inadequate scope and fast-tracking of the environmental impact statement.

Rush Order

The Corps is pushing full-steam-ahead to publish the final EIS. How fast are they moving? Let’s consider Pebble Mine’s closest comparison, Donlin Gold Mine in Alaska. The entire process for Donlin took six years, including two-and-a-half years for the draft EIS and five months for public comments. Comparatively, the Pebble Mine process is set to complete in two years, including a nine-month draft EIS and 90-day comment period.

According to Wild Salmon Center, the two-year permitting schedule set by the Corps “highlighted where they plan to skip steps in the [National Environmental Policy Act] process that would typically have been part of the EIS development.” This rush through the permitting process is highly concerning, especially given missing data and disregard for community and scientific input.

Missing Data

Important information has been omitted by both Pebble and the Corps. Pebble did not submit several documents that are usually included with mining applications, including an economic feasibility study, wetlands impact report, and plans for the mitigation of water impacts, reclamation of wetlands, and post-closure procedures. A former environmental scientist for the mining company Rio Tinto provided an independent economic feasibility analysis, which estimates the Pebble Mine plan would lose $3 billion and is “almost certainly not economically feasible.” Without a realistic plan to review, the Corps is not accurately assessing the environmental impacts of the mine. Additionally, the Corps has not conducted a human health impact assessment. Although not required, such an assessment is certainly recommended and desired.

Poor Cooperation

Groups that should receive an invitation to collaborate instead receive the cold shoulder. EPA experts have requested to be included in the EIS process, but the Corps essentially cut the agency out of the loop. Internal EPA emails state the Corps and Pebble are “expediting review, eliminating steps, and limiting cooperating agency review and meaningful public participation.”

Only two of 25 federally-recognized tribes in Bristol Bay have been included in the EIS process. Both the Nondalton and Curyung tribes have used this inclusion to express concerns over permitting. Still, even groups at the table are not offered professional courtesies. The Corps refuses to sign agreements with cooperating agencies, a move that diminishes transparency and trust in the permitting process.

Underestimated Impacts

Pebble submitted a 20-year proposal for Pebble Mine. Behind closed doors, the CEO of its parent company reveals the true plan: This small-scale proposal is meant to gain traction for permitting while allowing the company to “expand the project beyond” the proposed timeline. If Pebble Mine were indeed to close after 20 years, the company would leave nearly 90% of the deposit untouched – an unlikely scenario. Still, the Corps’ evaluation ends at 20 years and does not consider the environmental impacts of, as the CEO describes, “many generations of mining.” The intention to expand could explain Pebble’s refusal to submit an economic feasibility study or post-closure plan.

With this short-term perspective, the Corps states, “Massive and catastrophic releases that were deemed extremely unlikely [in the 20-year plan] were… ruled out for analysis.” In other words, the EIS does not account for major breaks, nor does it sufficiently assess long-term contamination. Unfortunately, leakage over a long period of time is likely and a massive event is possible, especially considering the plan includes dam designs that have already failed in Canada and Brazil. A report by the Bristol Bay Seafood Development Association examined what would happen if the dam completely failed: The analysis showed mine waste would spread across 155 miles of salmon habitat and 435 miles of streams for salmon spawning and rearing.

Wild Salmon Center is not the only critic. The Department of the Interior states, “The [draft EIS] has major outstanding issues… There are also instances where [the Corps] failed to conduct or include important analyses and where effects are minimized or dismissed as not being ‘measurable’… the [draft EIS] is so inadequate that it precludes meaningful analysis.”

Long-Lasting Consequences

Bristol Bay stands to suffer considerably more harmful impacts than those identified in the Corps’ draft EIS. These impacts are discussed in a 2012 report by Wild Salmon Center and Trout Unlimited. (Note: The 2012 report assessed the original Pebble Mine proposal, which included 25-year and 75-year plans. The 2017 Pebble Mine proposal is based on a 20-year plan, hence the discrepancy between this section and the previous section.)

Changing Landscape

Even with its limited scope, the draft EIS does show 4,000 acres of wetlands and 80 miles of streams would be permanently removed from the ecosystem. These landscape changes are only estimated from the short-term plan submitted by Pebble. They do not account for long-term mining by Pebble and other companies. As of 2012, seven additional companies had claimed nearly 800 square miles of Bristol Bay for future operations.

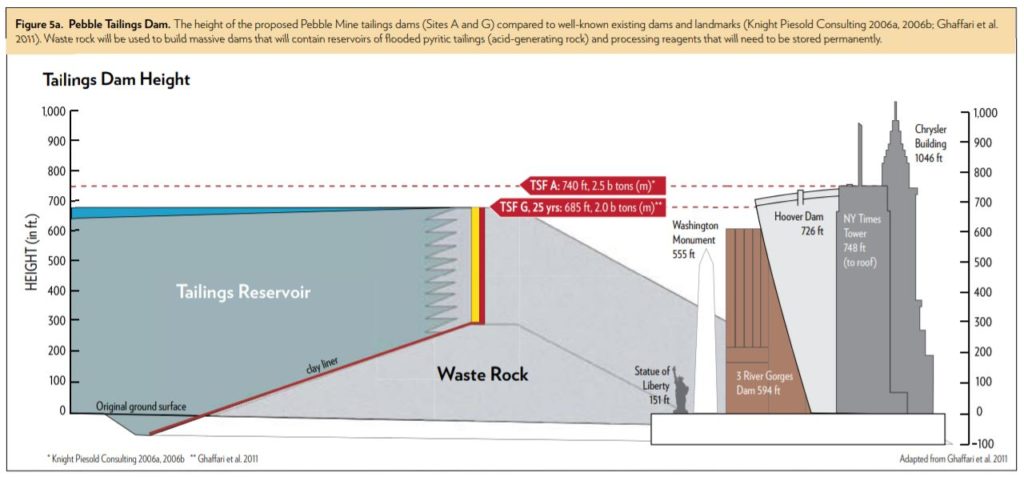

Mining will require much more than open pits. According to the Pebble plan, the operation will also need to draw substantial amounts of fresh water and energy, in addition to constructing new roads, pipelines, and ferries for processing, storage, transportation, and treatment. Speaking of storage, the 2014 Watershed Assessment by the EPA determined 99% of the Pebble deposit will be acid-generating waste. Pebble has suggested storing waste in tailings dams. Even under a short-term, 25-year plan, the operation would generate 2 billion tons of waste requiring a dam 700-740 feet high and four-and-a-half miles long. This would be as tall as the Hoover Dam and three miles longer than the Three River Gorges Dam.

Image from “Bristol Bay’s Wild Salmon Ecosystems and the Pebble Mine: Key Considerations for a Large-Scale Mine Proposal” by Wild Salmon Center and Trout Unlimited

Maintenance Required

Because of the mass of waste created, storage facilities will need regular upkeep to avoid erosion and leakage of toxic contaminants. Even so, the evidence for long-term mining maintenance is not comforting or convincing. Research on hundreds of North American mines demonstrates that all sulfide-containing mines, such as Pebble, damage water quality over time in spite of maintenance efforts. Even more concerning, Bristol Bay is subject to extreme weather and earthquakes, making experts concerned the infrastructure – including dams and pipelines – would not hold up. Even estimations for rainfall and snowmelt used to design dams may not be accurate due to climate change.

As for water impacts, Pebble has estimated 1.8-10.6 billion gallons of water waste will need to be treated each year – an amount surpassing any U.S. mine in operation today. The 2012 report supports findings from the draft EIS that polluted water would require on-going treatment “in perpetuity.” In other words, the Corps cannot predict when the water will be suitable and could require treatment for “hundreds or thousands of years.”

Soil and Water Contamination

Any infrastructure damage would lead to ecosystem damage. Given the area’s extreme weather, pipes are at risk of breaking if a pump failure causes their contents to freeze. Leaks could spread incredibly far, since the Pebble Mine plan shows pipelines will cross nearly 90 creeks and rivers.

Metal sulfides in the Pebble deposit also put the region at risk of acid mine drainage. The combination of metal sulfides with air and water erode surrounding rock, releasing harmful minerals that can travel far beyond the mine site. Acid mine drainage harms fish by impairing their ability to breathe and killing off food sources like insects. Any type of mine drainage in groundwater, surface water, and soil could be toxic to people, animals, and the environment. Every mining site with similar dams has leaked toxic contaminants in the long-term.

Even daily operations pose a threat. The Pebble deposit contains several metals – arsenic, copper, mercury, molybdenum, and lead – with potential to harm the ecosystem and humans if they spread as toxic dust. Copper, for example, dampens salmons’ ability to smell, hindering the fish from navigating, sensing predators, and finding mates.

Seafood Losses

The Pebble deposit is located where the Nushgak and Kvichak rivers meet the ocean – an area comprising more than half the land of Bristol Bay, producing more than half its salmon, and supporting 35 species of fish. Any incident would endanger the fish population and the livelihood, if not the health, of the community. Twenty-five tribes living in Bristol Bay rely on salmon for their subsistence fishing. The Athabaskan, Aleut, and Yup’ik peoples alone harvest 150,000 salmon per year to eat and store for winter. These communities feed their families with a tradition now threatened by the dangers of Pebble Mine.

In addition to food, local and seasonal fishers are at risk of losing income. Major salmon losses would devastate the $1 billion commercial fishing industry as well as the recreational fishing industry, which contributes more than $100 million to the Alaskan economy each year.

Historical Context

History is littered with examples of mining mishaps. In a recent study of U.S. mines, the Associated Press found that 43 mine sites leak over 50 million gallons of contaminated wastewater every single day, often into groundwater and rivers. For example, the Holden Copper Mine in Washington closed in 1957, leaving 8.5 million tons of waste in storage, underground flooding with acid drainage flowing into a nearby creek, water contaminants unsafe for salmon, and soil contaminants unsafe for people. Damage-control for Holden Copper Mine is estimated to cost $107 million – more than 20% of the mine’s total earnings.

In addition to chronic leakage, catastrophic incidents are fairly common. In 2000, a Martin County Coal Corporation reservoir failure sent 300 million gallons of waste into 75 miles of Kentucky waterways, costing an estimated $45-60 million. Nearly 400,000 fish died and residents along the Tug River were unable to drink local water. In Brazil just last year, 2.5 billion gallons of sludge from a dam collapse buried part of a town, leaving 270 people dead. In the case of Bristol Bay, the rushed EIS process does not convince us that Pebble and the Corps are taking sufficient care to avoid such disasters with Pebble Mine.

Save What You Love – Take Action

Slow Food stands with the Bristol Bay community in their efforts against Pebble Mine, especially in light of the tragedies from past mining operations, concerns from local communities and seasonal fishers, and criticisms against the rushed and woefully inadequate draft environmental impact statement. We support the traditions and sustenance of Indigenous communities, the continuation of responsible fishing, and the stewardship of our ecosystem.

The Corps is scheduled to release its final environmental impact statement this summer – but we are not too late. We can all take actions to save what we love – the Bristol Bay community, the salmon, and the future.

This Week

- Sign this petition by Friday, May 15th urging Trump to stop Pebble Mine.

Upcoming & Ongoing

- Watch The Wild virtual film screenings starting on June 5th – details to be posted here.

- Tune into Slow Fish Crew Together: The Story of Salmon on June 5th.

- Send this message to your elected officials to halt the permitting process by simply entering your information and submitting.

- Follow Save Bristol Bay on Facebook and Instagram.

- Subscribe to the Protect Bristol Bay Newsletter for the latest updates from the front lines.

I have serious misgivings about the validity of the EIS submitted for the Pebble Mine Proposal based on insufficient data collected on the environmental and human health impacts, lack of transparency about the process, and omission of key stakeholders (tribes who use the region). The long-term consequences on the health of inhabitants of the area are serious. If decision makers cannot see themselves living out the consequences, then why are they subjecting others to that risk for personal greed?